Emotional Intelligence

Reflection Questions

Were you allowed to express emotions as a kid? Which ones?

What were you taught about how men handle emotions?

Are there emotions you have difficulty letting yourself feel?

On a spectrum of stuffing emotions to getting swept away by them, where do you typically lean?

What are emotions?

Think of emotion as your mind tagging things with value so that it can initiate a response.

It goes like this: you experience stimuli in your environment (like a loud noise), in your body (like a pain), or in your mind (like a random thought). Your mind attempts to make sense of that stimuli by referencing it against past experiences and filtering it through established constructs (like narratives, beliefs, and prejudices). The mind looks for patterns so that it can assign values and make predictions, which then inform a physiological and behavioral response. It sends signals to the body, and before you know it, you’re feeling something and acting accordingly.

What we call emotions are the descriptive labels we use to describe the feelings and behaviors that have been triggered.

That initial processing happens subconsciously and in a millisecond. So before your rational analysis can make sense of the state you’re in, you’re already in that state. In other words, before you know to say “I’m scared”, your brain has already sped up your breathing, increased blood flow, released adrenaline, etc. You’re also likely in the early stages of fight, flight, freeze, fawn, or shut down without having made any conscious choice.

Your processing might become more conscious and deliberate, but that doesn’t mean it’s divorced from the emotional system. Consider how our “thinking” behaviors (like ruminating and intellectualizing) are often coping strategies to deal with underlying feelings. And consider the ways our “rational” beliefs are shaped by the initial subconscious judgements we make regarding which people to trust and which groups to defend. This is an example of how we use our reason to reinforce the emotional decisions we’ve already made, a phenomenon Jonathan Haidt refers to as “the emotional tail wagging the rational dog”. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking Fast and Slow, puts it this way: “We don’t think and then feel; we feel, and then we rationalize the feeling.”

Are emotions bad?

No. Emotions are an integral part of how humans navigate the world, allowing us to make the value judgments that guide our choices. Emotions also add color and dimension to life, arguably making it experientially worth living. But for many people, the “goodness” of emotion needs defending. There are several reasons for this.

One is the experience of being scolded at a young age for showing emotion, leading people to develop a pattern of suppression. Another is the experience of trauma, leading people to disconnect from their bodies and avoid emotion out of fear of being overwhelmed. Yet another is the ideological or religious demonization of emotion, found in shibboleths like “facts don’t care about your feelings” and sermons on Jeremiah 17:9 (“The heart is deceitful above all things”).

But one of the most significant culprits is the gendering of emotion within the system of patriarchy (see Bell Hooks on this subject). In this framework, emotion is associated with femininity, and femininity is associated with weakness, which is something men are taught they can never be. To be strong is to be non-feminine, which is to be non-emotional. This framework is so ingrained in our culture that the trope of “men are rational while women are emotional” is rarely challenged, despite it being demonstrably false. (Go to a sporting event or any social media platform and tell me men aren’t emotional. Ask a mom about her system to get kids where they need to be and tell me women aren’t rational.) There’s a rich conversation to be had about how and why emotion gets expressed differently in men and women. Likely, there is a complex relationship between biological realities, contextual factors, and social conditioning. But men will struggle to have that conversation if they can’t first be convinced to accept the goodness of their own emotionality.

Of course, the irony is that the most sure-fire way to be ruled by one’s emotions is to be in denial of them. So in trying to project a faux ideal of stoic rationality, men are more susceptible to having an emotional undercurrent drive their behaviors.

Should I trust my emotions?

Yes and no. Give your emotions respect, but not ultimate authority. Your emotions are real in the sense that the mind’s reactions are real. If your fear response is triggered, something measurable is actually happening, and it doesn’t do any good to pretend it’s not. This applies to others as well. We don’t get to tell someone their feelings aren’t real or that they shouldn’t be feeling what they’re feeling.

Instead of saying “I’m not feeling this” or “I shouldn’t be feeling this”, be curious about why the particular response is happening. (Note: you may need to regulate your nervous system before you’re able to do this level of rational processing.) You may gain insight into the trigger that helps you see what a constructive response would be. You may also discover that your mind made a connection that isn’t really there or triggered a response that’s disproportionate to the actual threat. Whatever you discover, you’re treating emotions as information, or a signal, telling you something is happening and/or something needs attention. Your grounded Self gets to decide what you want to do with that information.

Increasing Awareness

One of the cool things that sets humans apart is our capacity for metacognition, which is the ability to think about our thinking. Unlike other animals (as far as we know), we’re able to get observational distance from our own inner worlds and behaviors. That level of awareness gives us agency. So instead of moving through life driven by appetites and instincts, we’re able to make conscious, meaningful choices. In therapy we call that being responsive, not reactive. And that’s the goal. As Viktor Frankl said, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

The first step is building awareness in three categories: our bodies, our behaviors, and our thoughts. As a therapist, I can start in any one of those places and help a client name the emotional state they’re in.

Paying attention to the body allows you to notice the physiological responses the mind has triggered, then reverse-engineer what’s happening. Maybe you notice that your breathing has become quicker, or that you’re holding your breath altogether. Maybe you start to feel hot or dizzy. Maybe you notice you’ve started to turn inward or that you’re shrugging your shoulders. Maybe you feel tightness in your stomach or a rush of blood to the head. Maybe you feel the impulse to get big and your eyes widen. If you can notice those changes happening, you can gain agency over what comes next.

Behaviors provide the next category of clues. Maybe you notice you’re being extra short with people or avoiding people altogether. Maybe you’re reaching for your phone a lot or making indulgent purchases. Maybe you’re sleeping more than usual. Maybe it’s the opposite. Maybe you’re energized and starting new projects. What do these behaviors signal?

Finally, your thought patterns can tell a story. Maybe you notice you’re fantasizing about someone or replaying an interaction. Maybe you’re ruminating on a mistake you made. Maybe you’re building a narrative about how you were wronged.

If you can hold these things together, it becomes extra illuminating. When you focus on the memory of the mistake you made, what sensation shows up in your body? What do you feel like your body wants to do? Hide? Shrink? Fight? What does that tell you?

Increasing Vocabulary

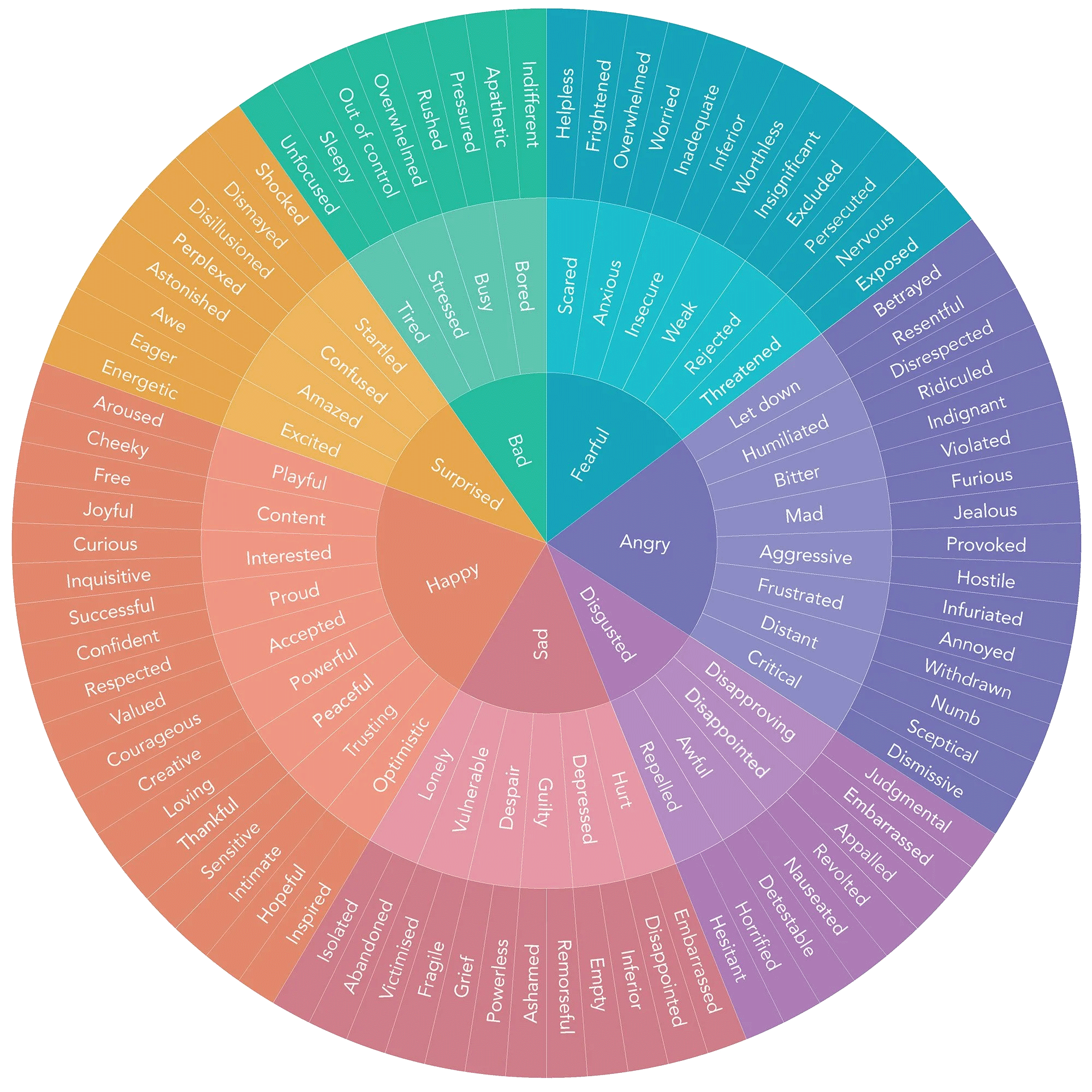

As you grow in emotional awareness it helps to grow your vocabulary so that you can communicate how you’re feeling with more accuracy. Consider the difference between mindlessly flying into a rage and articulating your anger. Now consider the difference between telling your partner you’re angry and calmly telling them you’re feeling humiliated or disrespected. The specificity offers a roadmap for them to meet you in your experience.

One of the ways to increase your emotional vocabulary is to increase your overall vocabulary through reading and engagement of the arts. Poetry, in particular, sharpens our ability to link sensations, abstract thought, and illustrative terms.

Another helpful tool is a feelings wheel (pictured above), which is like a pie chart divided into core emotions with increasingly specific language as it moves outward from the center. There are various iterations of a feelings wheel, with people putting different core emotions in the center and adding their own corresponding terms. A unique and helpful variation was created by therapist Lindsay Braman (linked at the top), which replaces the terms on the outer ring with corresponding bodily sensations. Yet another variation is Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotion (linked at the top), which names eight core emotions and explores their relationship to one another.

Finally, journaling can be a helpful exercise, giving you space to work out your emotions without the pressure of getting the language exactly right in conversation. If you’re curious about journaling, I recommend exploring The Artist’s Way and the practice of Morning Pages.